5 DIY Gut Health Tests You Can Do At Home (For Free)

We talk about gut health a LOT... So you might be wondering just how healthy yours is. Especially because it has such a big impact on almost every aspect of our overall health, including our immune system, allergies and sensitivities, autoimmunity and even our weight. And while we can do proper functional lab tests to identify conditions like SIBO, Leaky Gut, dysbiosis and infections like parasites, candida and bad bacteria, there are a few DIY Gut Health Tests you can do at home to get an idea of the state of your gut health and see if there are clues about whether you need proper testing.

Yes, perving on your own poop is part of the deal. But, these DIY tests are basically free and will give you an amazing insight into the health of your inner eco-system.

A recent video I created on DIY gut health test you can do at home for those who prefer to watch, rather than read:

1. THE TRANSIT TIME TEST

What is it and what does it tell us?

“Bowel transit time” is the time it takes for the food we eat to travel through our digestive system and get eliminated in a bowel movement (1). That is, how quickly your dinner goes from table to toilet. The ideal bowel transit time is anywhere from 12 to 48 hours, with variations telling us one of two things:

1. Too slow: Anything longer than 72 hours is considered a sign of constipation and can indicate imbalanced gut flora, toxin build-up and increased risk of fermentation (gas and bloating), SIBO and pathogenic infections (2, 3).

2. Too fast: A rapid transit time of less than 10 hours means your food is passing through your digestive system too quickly and that you might not be absorbing the nutrients from your food properly (4). In addition to nutrient deficiencies, this might also be a sign of some more serious conditions like IBD, Ulcerative Colitis, Celiac Disease or Crohn’s (5).

How it works

While a doctor might use dyes that show up on an X-ray, we can do a similar test at home using a ‘food marker’ - something that will easily show up in your stool. Here’s how:

1. Do not eat the food designated as the marker for a week before you do the test

2. Eat one of the following food markers:

> Corn kernels - one cup of cooked corn, eaten alone about an hour away from other food.

> Sesame seeds - two teaspoons of sesame seeds, mixed into a glass of water and swallowed whole, eaten alone about an hour away from other food.

> Red beetroot - one cup of cooked beetroot, eaten alone about an hour away from other food

3. Record the date and time you eat the food marker

4. Be on the lookout for the food marker in your stool and record the date and time you first pass it in a bowel movement

5. Calculate the time between #3. and #4. and compare to the ideal range of 12-48 hours.

Here’s a few things to note:

> Men tend to have faster transit times than women, even when eating the same diet (6)

> Some foods will naturally move slowly or quickly through our digestive system depending on their fibre and water content, as well as on what else we have eaten or drunk the same day (water, caffeine, alcohol, etc.)

> Given the many variables affecting transit time, it is recommended you complete the transit time test three times and at different times of the day to get a better average measurement to go on.

2. FREQUENCY MEASUREMENT

What is it and what does it tell us?

Although there isn’t a ‘perfect’ number of bowel movements you should have per day, aiming for once a day is a good place to start. Medical guidelines suggest that anywhere from three times per day to three times per week is within ‘normal’ range (7). Any more could indicate problems with malabsorption and any less than once daily, in our clinical opinion, could indicate (as with slow transit time) constipation and imbalanced gut flora, toxin build-up and increased risk of fermentation (gas and bloating), SIBO and pathogenic infections.

How it works

The easiest way to measure this is with a ‘poop diary’ over a two-week period. Simply make a list of the dates and times you have a bowel motion.

More important than frequency, is the ease with which you have bowel movements. If you need to push or strain, something is off, and normally closely aligned to the form of your stool (below).

3. BRISTOL STOOL FORM SCALE

What is it and what does it tell us?

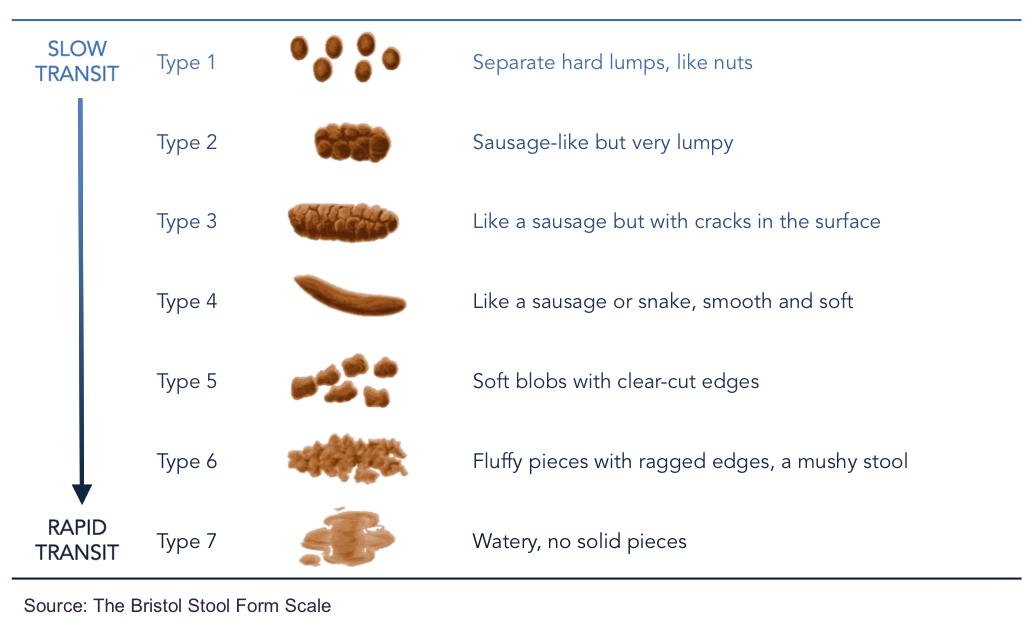

The Bristol Stool Form (BSF) Scale is a visual aid designed to classify faeces into one of seven categories (8). It was developed at the University of Bristol (hence the name) and first published in 1997, going on to become probably the most commonly used poop chart in the world.

Basically, the BSF Scale is another way to estimate bowel transit time - the longer it takes for poop to pass through your digestive system, the more dry, hard and compacted it becomes. But, this simple chart can also be used to identify potential gut dysfunction in a more targeted way…

Here’s each of the categories and what they can tell us:

Bristol Stool Form Scale Gut Health Poo Test DIY

Type 1 - Indicates problems with constipation from lack of fibre, low levels of beneficial gut bacteria or recent use of antibiotics

Type 2 - Can be a symptom of IBS and long-term chronic constipation

Type 3 - May indicate latent constipation

Type 4 - Optimal

Type 5 - May indicate incomplete digestion of food (especially if food particles are visible), or not enough fibre or carbohydrates to feed the good gut flora

Type 6 - Indicates abnormally rapid transit time and can be the result of stress, medications, laxatives or a gut disorder

Type 7 - This is typical diarrhoea and usually results from food poisoning or waterborne gut infections, but can also be the result of ‘bypass’ or ‘overflow’ diarrhoea resulting from severe constipation or faecal impaction.

How it works

As with all of these tests, consistency is important. A one-off stool type may be nothing to worry about, but frequently experiencing stools that match Type 1 or 2 and Type 6 or 7 may indicate a problem that should be investigated with further testing.

4. VISUAL INSPECTION

What is it and what does it tell us?

Beyond the ‘form’ of the stool, what you see when you look down in the toilet bowl can be an important indicator of gut health. Here are a few things to look for:

> Colour - brown is best. One-off discolouration might simply be from the food/supplements you are eating (like beetroot, charcoal or iron supplements) but more consistent light or dark stools may be cause for further investigation. Light coloured stools (pale, clay or grey) may indicate low iron levels, fat malabsorption or poor bile production, while dark stools may be the result of diet, supplements, lack of hydration or an underlying gut dysfunction. Obviously blood in your stool is not a good sign and means you should get a medical check-up.

> Mucous - visible mucous that looks like a slimy gel on your poop may be a sign of inflammation in your digestive tract. It may also indicate other conditions such as a gut infection, gluten sensitivity or inflammatory bowel disease (9).

> Floating - stools that float to the surface in the toilet are most often caused by diet-induced gas, but can also be the result of lactose intolerance or more serious diseases such as bowel infections or pancreatic and gallbladder diseases (amongst others). Generally, floating stools are nothing to worry about but if it becomes a consistent thing and is associated with other IBS symptoms, it may point to an underlying disorder or bacterial imbalance (10).

> Undigested food particles - So, we have already learnt above that not all foods are fully digestible - i.e. corn, beetroot, seeds, etc. But, for foods that should be easily digested, undigested food can also indicate intestinal inflammation, low levels of hydrochloric acid in the stomach, pancreatic enzyme deficiency, poor nutrient absorption or other gut dysfunction.

How it works

Poop and peek… pretty simple. Be on the lookout for any changes in colour, mucous, floaters and undigested food particles. If you notice anything odd, get it checked out.

5. THE SNIFF TEST

What is it and what does it tell us?

Normal poop smells. But what we care about is poop that is strangely smelly, or foul. Poop generally smells because of the toxins and bacteria being excreted… all normal. But, particularly noticeable changes can be an indication of fat malabsorption, undigested food particles or even a parasite like Giardia - for those with the rotten egg/sulphur variety of stench (11).

How it works

Again, it’s about consistent change. Diet and medications can have an effect so don’t freak out at the odd odour. But if it hangs around (like a bad smell…) then you might want to investigate further.

NEXT STEPS

So, you perved at your own poop and didn’t like what you saw. Maybe it was the slow transit time or sense of Déjà Poo from seeing too much of last night’s dinner make a reappearance. Whatever it is, having a proper functional lab test done might be what you need.

The test we generally have our client’s complete is a comprehensive assessment of the microbiological environment of the gut. It reports on bad (parasites, bacteria and yeast/fungus) and imbalanced organisms, as well as identifies the levels of beneficial flora that you need to be healthy. This is done using DNA detection of a stool sample, rather than the traditional visual microscopy approach, meaning it is much more accurate and only one sample needs to be collected - winning!

If you’re interested in getting tested, please get in touch. Healing the gut is a journey. If you are ready to begin yours, please head to the Work With Us page to learn more about how we work online with clients in many countries to test for and treat the many root causes of IBS symptoms and other GI conditions.

Did you find this post on DIY Stool Tests helpful? Want to get back to this post later? Save THIS PIN below to your Gut Healing board on Pinterest!

References:

Lee, Y. Y., Erdogan, A., & Rao, S. S. C. (2014). How to Assess Regional and Whole Gut Transit Time With Wireless Motility Capsule. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 20(2), 265–270

Choi, C. H., & Chang, S. K. (2015). Alteration of Gut Microbiota and Efficacy of Probiotics in Functional Constipation. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 21(1), 4–7

Bures, J., et al. (2010). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, 16(24), 2978–2990

Roy, S., Akramuzzaman, S., Akbar, M. (1991). Persistent diarrhea: total gut transit time and its relationship with nutrient absorption and clinical response. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 13(4), 409-14

Waugh, N., et al. (2013). Faecal calprotectin testing for differentiating amongst inflammatory and non-inflammatory bowel diseases: systematic review and economic evaluation. NIHR Journals Library, Health Technology Assessment, No. 17.55. Appendix 1, Comparison of ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, irritable bowel syndrome and coeliac disease.

Probert, C. J., Emmett, P. M., & Heaton, K. W. (1993). Intestinal transit time in the population calculated from self made observations of defecation. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 47(4), 331–333.

Thompson, W., et al. (1999). Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut, Suppl 2, II43–7

Lewis, S., Heaton, K. (1997). Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol, 32(9), 920-4

Hendrickson, B. A., Gokhale, R., & Cho, J. H. (2002). Clinical Aspects and Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 15(1), 79–94

Bouchoucha, M., Devroede, G., Benamouzig, R. (2015). Are floating stools associated with specific functional bowel disorders? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 27(8) 968-73

Amin, N. (1979). Giardiasis: a common cause of diarrheal disease. Postgrad Med, 66(5), 151-8.