Why Dairy Might be Causing Your Digestive Distress

I don’t eat dairy. I don’t hate dairy either. It just doesn’t agree with me. But that wasn’t always the case. Six years ago I was drinking milk for breakfast, eating yoghurt for a morning snack and munching my way through multiple serves of cheese every day. But, I was also chronically constipated, had horrible skin and a constantly running nose.

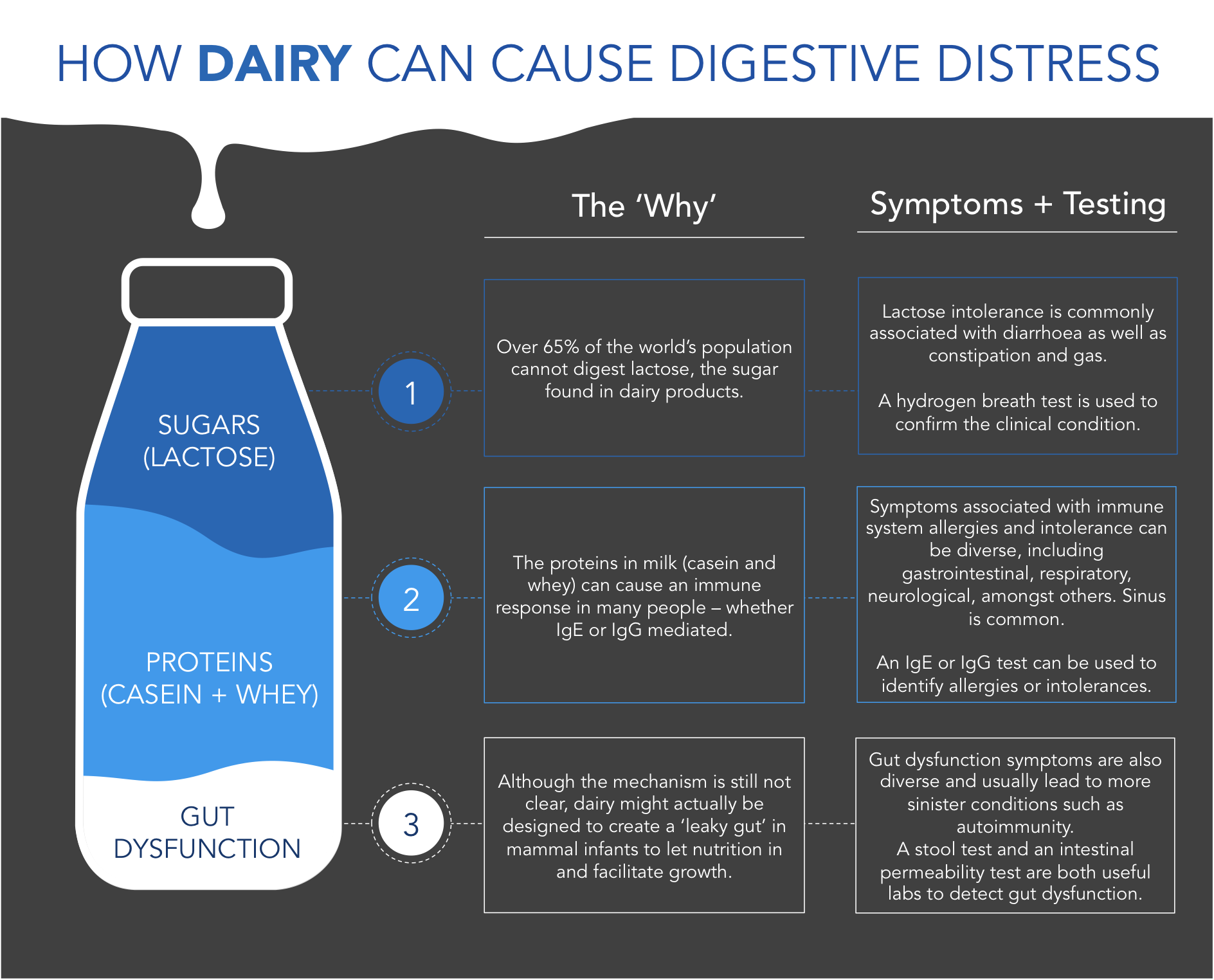

And if you consider yourself somewhat of a dairy queen, it might just be the reason you’re experiencing digestive issues and IBS symptoms. While the health benefits of modern, processed dairy are still very much up for debate, there’s no disputing the gastrointestinal effects dairy can have on many people. And it’s more than just lactose intolerance that might be to blame.

Here is a summary of what we are going to cover:

> Three reasons you might not be able to digest lactose

> What FODMAPs and SIBO have to do with dairy

> How dairy proteins can cause immune reactions and IBS symptoms

> Why milk might actually be designed to cause a leaky gut

(Click to view full size)

How Dairy Can Cause Digestive Distress

SUGARS (LACTOSE)

Lactose intolerance is actually an enzyme deficiency, not an allergy. The enzyme that breaks down lactose into glucose and galactose (simple sugars) is lactase. Without lactase, undigested lactose can make it’s way to the large intestine (lactose malabsorption) and cause digestive upset in many people (lactose intolerance).

LACTOSE MALABSORPTION

A lactase enzyme deficiency, leading to lactose malabsorption, can happen for one of three main reasons:

Lactase Non-Persistence: While lactase production is essential for infants during breastfeeding, lactose production usually declines after the weaning period is over (1). While the majority of the human population lose the ability to digest lactose from around age 4 or 5, around 35% of people continue to produce lactase throughout adolescence and even into adult life (2). These lucky few can digest the lactose found in dairy products. This evolutionary trait, known as lactose persistence, is more common amongst Europeans and other cultures that started domesticating animals and milking cows around 8,000 years ago (3).

Damaged Intestinal Lining: Lactase deficiency also occurs as a result of damage to the epithelial cells lining the intestinal walls, which are responsible for producing lactase in the gut (4). Conditions such as coeliac disease or intestinal infections such as bacterial, parasitic or yeast overgrowths can all result in a damaged or ‘leaky’ gut and impaired lactase production. This type of deficiency is commonly reversible after recovery from whatever condition is causing the damage in the first place (5).

Dysbiosis of Gut Bacteria: Certain types of gut bacteria, including lactobacillus and bifidobacteria, produce lactase and other enzymes that help us break down and absorb lactose (6, 7). However, if your gut flora doesn’t have the right species or is overrun with the wrong ones, you might struggle to digest dairy products containing lactose (8). This kind of dysbiosis can happen for many reasons, the most common of which include; antibiotics, intestinal infections (bacteria, parasite, yeast), stress, toxins and eating a processed-food diet.

And just so you know, it is very interesting to note that raw (unpasteurised) milk actually has lactase enzymes in it that help break down the lactose once it gets to your gut - nature is pretty smart like that. However, in our pursuit to kill bacteria of all varieties (good or bad), the rapid heating of milk (pasteurising) kills off the lactase, making it increasingly difficult for many people to digest commercial dairy products (9). While farmers are allowed to drink their own raw cow’s milk, Australia is one of only two countries in the world where it is illegal to sell raw milk for human consumption. So, until the laws change, getting access to raw dairy that has the lactase enzymes in it, and is easier for us to digest, means owning a cow.

LACTOSE INTOLERANCE

Lactose malabsorption and intolerance are not the same thing. While malabsorption describes the body’s inability to break down lactose in the small intestine, intolerance is the reporting of gastrointestinal symptoms including abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence and diarrhoea (4).

Lactose that is not broken down properly and that reaches the large intestine (malabsorption), will not necessarily cause symptoms, with only some malabsorbers reporting them. And with certain conditions, the lactose doesn’t need to make it past the small intestine for intolerance symptoms to develop. So, you can have malabsorption without intolerance and intolerance with malabsorption… or both. Are you still with me? Here is the really interesting part:

Enter two acronyms that anyone with IBS is probably familiar with - FODMAPs and SIBO. Let’s look at each in a little more detail.

FODMAPs - Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols: FODMAPs are sugars, found in many everyday foods, that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine and reach the large intestine where they produce gas and attract water. With a sensitivity to FODMAPs, bacteria located in the large intestine ferment specific types of carbohydrates, leading to gas, bloating, diarrhoea and other IBS-type symptoms (10). It should be no surprise to learn that lactose is one of the these carbohydrates - a disaccharide, to be exact. So, for lactose malabsorbers with the wrong balance of bacteria in the large intestine, lactose often results in gastrointestinal symptoms.

SIBO - Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: While it’s normal to have bacteria in your intestines, most of them should be in your large intestine, not your small intestine. SIBO occurs when bacteria from your colon (large intestine) overgrow into your small intestine (11). These bacteria aren’t necessarily bad, they are just in the wrong place. And with this bacteria in the wrong place, fermentation can happen in your small intestine, rather than in the large intestine, as discussed above. With lactose being one of these fermentable carbohydrates, those with SIBO might still experience IBS symptoms regardless of whether they are lactose malabsorbers or not.

PROTEINS (CASEIN + WHEY)

There are six types of protein in cow’s dairy; four types of casein (found in the solid part) and two types of whey (found in the liquid part). Among these different types of proteins are numerous ways for humans to experience adverse reactions.

Allergy (IgE mediated): Allergy to the proteins in dairy (more commonly casein than whey), often referred to as cow’s milk allergy (CMA), is the most common food allergy in early childhood (12). This ‘true’, or IgE mediated allergy is estimated to affect around 5% of young children but progressively decrease in prevalence with age (13). This milk-induced allergic reaction can include itchy skin, hives, rashes, diarrhoea, stomach pains and breathing difficulties, among other symptoms. This is a more life-threatening condition than the general intolerances we are used to seeing in clients with IBS.

Intolerance (IgG mediated): A food intolerance to dairy is the most common IgG mediated immune response I see in patients with IBS - affecting up to two-thirds of those tested. The main culprit is a specific type of casein, known as A1 beta-casein, most commonly present in the high-producing Holstein cows favoured by American, Australian and Western European industrial dairies. A1 casein is thought to represent a mutated form of protein, appearing around 5,000 years ago, after the onset of agriculture and animal domestication (14).

It is this A1 casein that releases an opiate-stimulating compound called casomorphin, found to cause gastrointestinal inflammation as well as delayed transit time (i.e. constipation) in some people (15). While destructive on its own, A1 casein’s interaction with lactose can cause further issues. Firstly, the inflammatory effects of A1 casein may affect lactase enzyme production and increase malabsorption. Secondly, the delayed transit time (constipation) may lead to increased opportunity for lactose fermentation in either the large or small intestine - the perfect recipe for gastrointestinal symptoms.

By contrast, milk that is exclusively A2 casein has been shown not to produce similar inflammatory and transit time reactions (15). Milk from Jersey cows as well as goats are traditionally A2 and a good starting point for those struggling with dairy products. The Australian dairy industry unfortunately switched to A1-producing cows in the 1970’s. This might help explain why we are all struggling today, while our parents were drinking milk like it was going out of fashion with no such problems.

Gluten cross-reactivity: Recent studies have concluded that casein is involved in setting off IBS symptoms for coeliac patients on gluten-free diets (16). Because of what are known as cross-reactive antibodies, the same antibodies created against gluten might also react to other foods, including (most commonly) cow’s milk. Meaning, when you eat dairy, your body still thinks you're eating gluten, and reacts accordingly. Not cool.

GUT DYSFUNCTION / LEAKY GUT

Not only can dairy cause fermentation through lactose malabsorption and immune reactions to proteins such as A1 casein, it can also cause increased intestinal permeability, a.k.a. ‘Leaky Gut’. There are many different mechanisms through which dairy might cause a leaky gut, including:

> Protease inhibitors cause digestive enzyme imbalances and an overproduction of trypsin, an enzyme that destroys the connections between the intestinal cells (17, 18)

> The inflammatory effects of A1 casein on the intestinal lining may increase the permeability of the gut lining (15).

While the science is still unclear on the exact mechanism, it is worth considering the idea that dairy is actually designed to create a leaky gut. That is, in newborns, a leaky gut may be essential to getting all the nutrients and other vital growth factors of mother’s milk directly into the bloodstream. Helpful for babies, not so much for adults who are exposed to harmful toxins and undigested food proteins that you really don’t want in your bloodstream. This might be one of the reasons that humans (and other mammals) are only designed evolutionarily to drink their own species’ milk as growing infants and not into adulthood. Food (or milk) for thought...

How do we go about figuring it all out? Testing is key.

TESTING OPTIONS

There are a few things you can do when trying to figure out why dairy might be causing you issues. First, you should try simply eliminating all dairy from your diet for a period of 5-7 days and see how you feel. Any changes with your digestion? Skin? Sinus issues gone away? Chances are, some part of the dairy you are eating or drinking doesn’t work for you. As we know, it might be because of the proteins or sugars in the dairy, the way the dairy you are eating is processed or it might be because of more deep-seated issues with your gut.

At this point, we would likely start with an IgG Allergy Panel (dry blood spot). This test is used to screen for 96 specific foods, including cheese, milk (cow and goat) and yoghurt. It also looks for an immune reaction in the body to casein and whey proteins. It doesn’t look for lactose intolerance so if you want to test for this you will need to complete a hydrogen breath test.

Following that, if there are markers that indicate more extensive gut issues then we would proceed with further testing. This is to determine the underlying root cause of your issues so that the variable food sensitivities (yep, they can change over time) that you may have to dairy can be eliminated. Then your gut can heal and you can start to incorporate small amounts of high quality dairy back into your life. Win win!

With all of that said, if you are worried about dairy and food sensitivities, and you want to get tested, please head to the Work With Us page to learn more about how we work online with clients in many countries to test for and treat the various root causes of IBS symptoms and other GI conditions.

References:

Wang, Y., et al. (1998). The genetically programmed down-regulation of lactase in children. Gastroenterology, 114(6), 1230-6

Morales, E., Azocar, L., Maul, X., Perez, C., Chianale, J., & Miquel, J. F. (2011). The European lactase persistence genotype determines the lactase persistence state and correlates with gastrointestinal symptoms in the Hispanic and Amerindian Chilean population: a case–control and population-based study. BMJ Open, 1(1), e000125

Gerbault, P., et al. (2011). Evolution of lactase persistence: an example of human niche construction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1566), 863–877

Wilt TJ, Shaukat A, Shamliyan T, et al. Lactose Intolerance and Health. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2010 Feb. (Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, No. 192.)

de Vrese M., et al. (2001). Probiotics--compensation for lactase insufficiency. Am J Clin Nutr, 73(2 Suppl), 421S-429S

Gaón, D., et al. (1995). Lactose digestion by milk fermented with Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus casei of human origin. Medicina (B Aires), 55(3), 237-42

He, T., et al. (2008). Effects of yogurt and bifidobacteria supplementation on the colonic microbiota in lactose-intolerant subjects. J Appl Microbiol, 104(2), 595-604

Zhong, Y., et al. (2004). The role of colonic microbiota in lactose intolerance. Dig Dis Sci, 49(1), 78-83

Van de Heijning, B. J. M., Berton, A., Bouritius, H., & Goulet, O. (2014). GI Symptoms in Infants Are a Potential Target for Fermented Infant Milk Formulae: A Review. Nutrients, 6(9), 3942–3967

Iacovou, M., Tan, V., Muir, J. G., & Gibson, P. R. (2015). The Low FODMAP Diet and Its Application in East and Southeast Asia. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 21(4), 459–470

Bures, J., et al. (2010). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, 16(24), 2978–2990

Fiocchi, et al. (2010). World Allergy Organization (WAO) Diagnosis and Rationale for Action against Cow’s Milk Allergy (DRACMA) Guidelines. The World Allergy Organization Journal, 3(4), 57–161

Solinas, C., et al. (2010). Cow's milk protein allergy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 23 Suppl 3, 76-9

Pal, S., Woodford, K., Kukuljan, S., & Ho, S. (2015). Milk Intolerance, Beta-Casein and Lactose. Nutrients, 7(9), 7285–7297

Jianqin, S., et al. (2016). Effects of milk containing only A2 beta casein versus milk containing both A1 and A2 beta casein proteins on gastrointestinal physiology, symptoms of discomfort, and cognitive behavior of people with self-reported intolerance to traditional cows' milk. Nutr J, 15:35

Vojdani, A., Tarash, I. (2013). Cross-Reaction between Gliadin and Different Food and Tissue Antigens. Food and Nutrition Sciences, 4(1), 20-32

Ohtani, S., et al. (2003). Evaluation of inhibitory activity of casein on proteases in rat intestine. Pharm Res, 20(4), 611-7

Bueno, L., Fioramonti, J. (2008). Protease-activated receptor 2 and gut permeability: a review. Neurogastroenterol Motil, 20(6):580-7